This post is adapted from my Conversation article of the same title originally published on 30/07/23

The UK is set to roll out a national lung cancer screening programme for people aged 55 to 74 with a history of smoking. The idea is to catch lung cancer at an early stage when it is more treatable.

Quoting NHS England data, the health secretary, Steve Barclay, said that if lung cancer is caught at an early stage, “patients are nearly 20 times more likely to get at least another five years to spend with their families”.

Five-year survival rates are often quoted as key measures of cancer treatment success. Barclay’s figure is no doubt correct, but is it the right statistic to use to justify the screening programme?

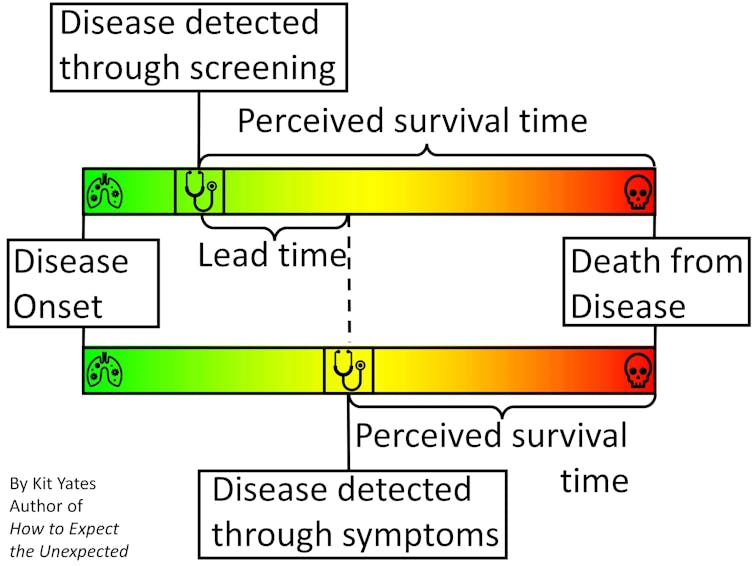

Time-limited survival rates (typically given as five-, ten- and 20-year) can improve because cancers caught earlier are easier to treat, but also because patients identified at an earlier stage of the disease would live longer, with or without treatment, than those identified later. The latter is known as “lead-time bias”, and can mean that statistics like five-year survival rates paint a misleading picture of how effective a screening programme really is.

My new book, How to Expect the Unexpected, tackles issues exactly like this one, in which subtleties of statistics can give a misleading impression, causing us to make incorrect inferences and hence bad decisions. We need to be aware of such nuance so we can identify it when it confronts us, and so we can begin to reason our way beyond it.

To illustrate the effect of lead-time bias more concretely, consider a scenario in which we are interested in “diagnosing” people with grey hair. Without a screening programme, greyness may not be spotted until enough grey hairs have sprouted to be visible without close inspection. With careful regular “screening”, greyness may be diagnosed within a few days of the first grey hairs appearing.

People who obsessively check for grey hairs (“screen” for them) will, on average, find them earlier in their life. This means, on average, they will live longer “post-diagnosis” than people who find their greyness later in life. They will also tend to have higher five-year survival rates.

But treatments for grey hair do nothing to extend life expectancy, so it clearly isn’t early treatment that is extending the post-diagnosis life of the screened patients. Rather, it’s simply the fact their condition was diagnosed earlier.

To give another, more serious example, Huntington’s disease is a genetic condition that doesn’t manifest itself symptomatically until around the age of 45. People with Huntington’s might go on to live until they are 65, giving them a post-diagnosis life expectancy of about 20 years.

However, Huntington’s is diagnosable through a simple genetic test. If everyone was screened for genetic diseases at the age of 20, say, then those with Huntington’s might expect to live another 45 years. Despite their post-diagnosis life expectancy being longer, the early diagnosis has done nothing to alter their life expectancy.

Overdiagnosis

Screening can also lead to the phenomenon of overdiagnosis.

Although more cancers are detected through screening, many of these cancers are so small or slow-growing that they would never be a threat to a patient’s health – causing no problems if left undetected. Still, the C-word induces such mortal fear in most people that many will, often on medical advice, undergo painful treatment or invasive surgery unnecessarily.

The detection of these non-threatening cancers also serves to improve post-diagnosis survival rates when, in fact, not finding them would have made no difference to the patients’ lives.

So, what statistics should we be using to measure the effectiveness of a screening programme? How can we demonstrate that screening programmes combined with treatment are genuinely effective at prolonging lives?

The answer is to look at mortality rates (the proportion of people who die from the disease) in a randomised controlled trial. For example, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) found that in heavy smokers, screening with low-dose CT scans (and subsequent treatment) reduced deaths from lung cancer by 15% to 20%, compared with those not screened.

So, while screening for some diseases is effective, the reductions in deaths are typically small because the chances of a person dying from any particular disease are small. Even the roughly 15% reduction in the relative risk of dying from lung cancer seen in the heavy smoking patients in the NLST trial only accounts for a 0.3 percentage point reduction in the absolute risk (1.8% in the screened group, down from 2.1% in the control group).

For non-smokers, who are at lower risk of getting lung cancer, the drop in absolute risk may be even smaller, representing fewer lives saved. This explains why the UK lung cancer screening programme is targeting older people with a history of smoking – people who are at the highest risk of the disease – in order to achieve the greatest overall benefits. So, if you are or have ever been a smoker and are aged 55 to 74, please take advantage of the new screening programme – it could save your life.

But while there do seem to be some real advantages to lung cancer screening, describing the impact of screening using five-year survival rates, as the health secretary and his ministers have done, tends to exaggerate the benefits.

If we really want to understand the truth about what the future will hold for screened patients, then we need to be aware of potential sources of bias and remove them where we can.